Design Change: Examples and Requirements

A design change is a change in the design of a product. It is important to understand what regulatory implications arise from this and where there may be an impact on the validity of the product's declaration of conformity.

This article provides an overview and thus resolves many currently common misconceptions.

Free infographic for download!

So that you can quickly and confidently decide whether a design change is significant in terms of the transitional rules of the EU regulations (MDR/IVDR) and thus avoid trouble with authorities.

1. Design change: What it means

a) Definition

According to the MDR/IVDR, a design change is always given if there is a change in the design of the medical device.

Design change is not only understood to be a change in a product's (graphic) design.

Rather, it is understood to mean any change to the design of a product before or after its respective release.

Caution!

Note that MDR and IVDR also interpret a change of intended use as a design change, even if the product remains completely unchanged.

b) Examples

One speaks of a design change, for example, when the manufacturer changes the following:

- the layout of a printed circuit board

- the user interface

- the functions offered by the product (because something has to be changed in the design as a result)

- performance specifications, e.g., the detection limit of an immunoassay or the energy output of an RF surgical device

- Materials from which the product is made

Suppose a software developer finds that the already released architecture contains a bug and changes it (implicitly in the code or/and explicitly in the architecture document). In that case, there is also a design change.

As already mentioned, MDR and IVDR also count a changed intended use, e.g., new indications or a different user group as a design change.

c) Regulatory requirements

FDA requirements for design changes

The FDA has found that when you solve problems, you often introduce new problems. Therefore, it requires that manufacturers evaluate these "solutions" (changes) very carefully before implementing them.

Specifically, :

Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures for the identification, documentation, validation or where appropriate verification, review, and approval of design changes before their implementation.

In discussing this paragraph, FDA points out the following:

1. Ensure documents are appropriately revised and managed (e.g., versioned and released).

2. Ensure, through verification and validation, that the problem this design change intends to solve is solved.

3. Ensure that the changes are approved and that it is evaluated that the change has caused no new problems and that the previous requirements are still met.

4. Communicate the changes so that other development departments, production, sales, and customers know about them.

Further Information

Read more about the Guidance Document‚Deciding When to Submit a 510(k) for a Change to an Existing Device‘ here.

ISO 13485 on design and development changes

Also in Europe, there are requirements for dealing with "design changes." Chapter 7.3 of ISO 13485, for example, requires that design and development changes be managed.

The requirements are similar to those of the FDA: The changes must be

- approved,

- evaluated,

- verified and validated, and

- documented.

MDR / IVDR

Both the EU Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) and the EU In Vitro Diagnostics Regulation (IVDR) address design changes in several places, for example, in:

- MDR Article 10 (9) / IVDR Article 10 (8): „Changes in device design […] shall be adequately taken into account in a timely manner.“

- MDR Annex VI, Part C, 6.5.2 / IVDR Annex VI, Part C, 6.2.2 (Software): „A new UDI-DI shall be required whenever there is a modification that changes the original performance; the safety or the intended use of the software; interpretation of data. Such modifications include new or modified algorithms, database structures, operating platform, architecture or new user interfaces or new channels for interoperability.“

- MDR Annex IX, 4.10 / IVDR Annex IX, 4.11: „Changes to the approved device shall require approval from the notified body which issued the EU technical documentation assessment certificate where such changes could affect the safety and performance of the device or the conditions prescribed for use of the device.“

2. Significant / substantial Design Changes: When a change must be reported to the notified body

Any planned design change must be evaluated within the QM system according to ISO 13485, Chapter 7.3. In the following, we describe when the notified body must also be involved.

Team NB Guidance Document

The Association of Notified Bodies (Team NB) has published a recommendation in NB-MED/2.5.2/Rec2, which is intended to provide more clarity on the communication of design changes to the respective notified body.

In this recommendation, the authors describe when a design change is to be considered substantial/significant and thus subject to notification to the notified body. This would be any change to the product that could influence conformity with the essential requirements, or the scope or contraindications specified by the manufacturer.

Specifically, the document specifies changes

- of the intended use, indication, contraindication

- of performance characteristics

- of a supplier(!)

- due to risks which have not yet been considered

- warnings

- the intended user groups

- of the intended utilization

- characteristics not yet considered by the clinical evaluation

- as a result of considerations arising from market surveillance, including incidents, recalls, or complaints

- driven by state-of-the-art development (e.g., latest technologies)

- affecting production

- that affect the safety and performance of the product

The notification obligation aims to give the notified body the possibility to check the conformity of the product after a design change. Notified bodies can decide on the basis of a reported product change whether to perform a new ad-hoc conformity assessment or to consider the change in the next scheduled audit.

At this point, the Team NB document only provides a general interpretation of substantial/significant changes. Since the document was still created under the MDD/IVDD, it is only an supportive under the MDR/IVDR. In any case, only the contract between the medical device manufacturer and its notified body, in which the notification criteria and conditions are explicitly and individually defined, is legally binding.

Scope of the certificate

The scope of the certificate is also critical: If you change your product, which you place on the market via Annex II of the MDD or via Annex IX of the MDR, in such a way that it no longer falls within the scope, you may not do so without involving the notified body.

The certificates just allow you, as a manufacturer, to develop and place products on the market within the certificate without asking the notified body for permission. However, the notified bodies often require to be informed.

3. Significant changes related to Article 120 of the MDR or 110 of the IVDR

From the previously described notification obligations for design changes to the notified bodies, another concept must be considered completely detached.

Significant changes in connection with the transition period from the European Directives (MDD/IVDD) to the Regulations (MDR/IVDR) are subject to other regulatory implications. Here, the issue is whether the previous declaration of conformity remains valid in the event of a change to the product.

In the context of the transitional regulations, the design changes in the regulations play a role at the following points:

MDR

By way of derogation from Article 5 of this Regulation, a device with a certificate that was issued in accordance with Directive 90/385/EEC or Directive 93/42/EEC and which is valid by virtue of paragraph 2 of this Article may only be placed on the market or put into service provided that from the date of application of this Regulation it continues to comply with either of those Directives, and provided there are no significant changes in the design and intended purpose.

MDR, Article 120(3)

IVDR

By way of derogation from Article 5 of this Regulation, the devices referred to in the second and third subparagraphs of this paragraph may be placed on the market or put into service until the dates set out in those subparagraphs, provided that, from the date of application of this Regulation, those devices continue to comply with Directive 98/79/EC, and provided that there are no significant changes in the design and intended purpose of those devices.

IVDR, Article 110(3)

To assist in the evaluation of changes to the product, the MDCG has published two guidelines. These specify criteria under which the changes are to be regarded as significant, and the declaration of conformity gets invalid.

a) MDCG 2020-3

In March 2020, the MDCG published "MDCG 2020-3" entitled "Guidance on significant changes regarding the transitional provision under Article 120 of the MDR with regard to devices covered by certificates according to MDD or AIMDD". This edition was later revised, supplemented with helpful examples, and published in May 2023 as "MDCG 2020-3 Rev.1".

Non-significant changes

The MDCG identifies what it does not consider to be significant design changes:

- Administrative changes

- Name and address of the manufacturer

- Legal form e.g., from GmbH to GmbH & Co. KG

- Authorized representative

- Organizational changes

- New production sites, relocation of production sites

- New or changed suppliers and service providers

- To a certain extent, also changes to the QM system

- Restriction of purpose

- Restriction of indications, clinical applications, or patient population

- Corrective actions

- Non-significant changes to the product that do not adversely affect the performance of the product, including changes that do not alter product internal control mechanisms, operating principle, power supply, or alarm systems, if applicable

For non-significant changes that explicitly do not adversely affect the benefit/risk ratio, the guideline gives the following examples:

Specification/marking

- Changes that narrow the certified range of specifications, such as screw length within the previous length or diameter

- Modifying the handle of a steerable ablation catheter to improve ergonomic comfort for medical personnel or the aesthetic appearance of a device

- Reformatting of an existing instruction manual

- Changing the label or packaging material of a non-sterile product

Components

- Replacing a semiconductor device/electronic component/assembly with the same specifications

- Applying a coating to a non-contact printed circuit board to improve current isolation

- Changing the size or geometric shape of control/alarm buttons

Power supply

- Change of a battery type

- Change of battery chemistry

- Change of charger or power cord with the same specification

Materials

- New or additional supplier/manufacturer of material within established specifications

- Substitution of a chemical substance to comply with other applicable laws and regulations, such as the REACH regulation

- Substitution of a substance or material that does not adversely affect the benefit/risk ratio, such as

- Improving the material quality without changing the specifications

- Replacing a material of the packaging of a sterile product that does not contribute to the maintenance of the sterile barrier

- Modification of a material that is considered only a processing aid and, therefore, a manufacturing change and not a design change

Sterility

- Change in sterilization cycle parameters, provided there is no impact on sterility assurance level or sterilization residuals

- Extension of shelf life, validated by procedures approved by the notified body

- Conversion from single sterile to double sterile packaging

MDCG 2020-3 states that manufacturers may ask for confirmation from notified bodies that a design change is not significant. However, this does not constitute a supplemental certificate.

Significant changes

MDCG defines the following changes as "significant":

- Expansion and changes in intended use, e.g., new indications, new patient population, different clinical application

- UI changes that require further usability data

- Changes to the performance specification

- Change in product dimensions or design features outside of current specifications, such as new stent lengths that are outside the range of previously certified stent lengths or the addition of electrodes to an implantable pacemaker lead

- Expanding specification limits for critical components or parameters

- Using new sensors with different operating principles, such as an air bubble detector using ultrasound versus an optical light sensor

- Design changes that either increase risks or affect existing risk mitigation measures

- Removing or adding an alarm system or handling an alarm situation

- Change from analog to digital control

- Change from a manual to a software-controlled device

- Replacing or changing materials, unless from existing suppliers and within unchanged specifications

- Change from a material with a low toxicological or biological risk to a material with a higher risk

- Addition or change of material of human/animal origin

- Changes to the sterilization process or packaging that may have an impact on sterility

- Change of the final sterilization method

- Change of a product from "non-sterile" labeling to "sterile" labeling

- Extension of shelf life that is not validated against protocols approved by the notified body

- Many software changes

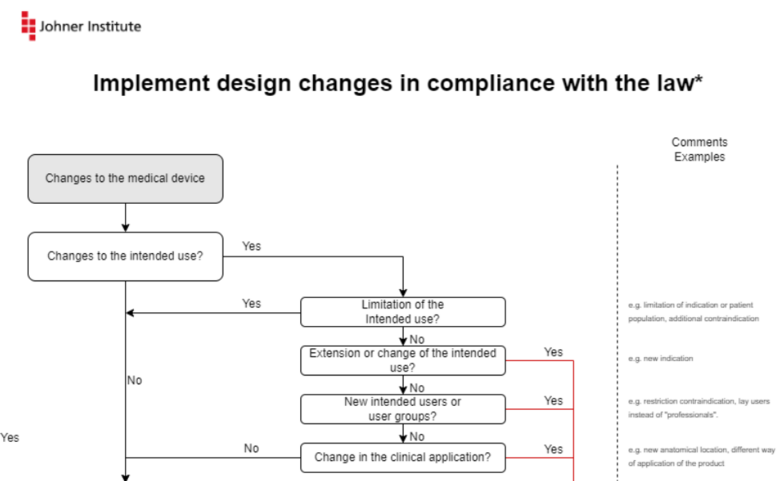

The MDCG describes the changes in the form of flowcharts. The Johner Institute infographic summarizes these diagrams on one page and adds examples.

You can download this infographic for free here: Download

Critics

The MDCG document is helpful. The revision has corrected formal deficiencies and also added many examples that have improved the usefulness of the guideline.

However, it leaves some questions open. Especially to the following questions, one would have wished for an answer:

- Do we really want to wave through all corrective measures (mind you, corrective measures, not corrections) even if they involve significant changes to the design? The order of the flowchart suggests exactly that.

- Why does one want to wave through corrective measures but not corrections? In software, bug fixes are not declared as "significant."

- Should every change to a "database structure" be considered significant? Every new column in a database?

b) MDCG 2022-6

Following the MDCG 2020-3 guideline for medical devices under MDR, the MDCG issued the MDCG 2020-6 guideline for in vitro diagnostic medical devices in May 2022 under the title "Guidance on significant changes regarding the transitional provision under Article 110(3) of the IVDR". It specifies which changes to a product that is subject to the transitional periods of the IVDR are to be classified as significant and builds on the provisions of MDCG 2020-3. Thus, the general specifications apply both to non-significant changes, such as administrative or organizational changes and to significant changes, such as extensions of the intended purpose or changes in the performance specification, also for the consideration of IVDs. In addition, however, in guideline MDCG 2022-6, the MDCG more specifically differentiates significant from non-significant changes by type of change, using examples:

- Change of intended use

- Non-significant

- Restriction of intended use, as by limitation of patient group

- Significant

- Any expansion of the intended use

- Change in intended use, such as a change in assay type from a qualitative to a quantitative assay or a change in sample type

- Non-significant

- Design changes

- Non-significant

- Design changes that do not alter the functional principle of the product, i.e., the assay method or detection procedure, including, for example, a change in a sample cleanup step or replacement of a PCR cycler

- Significant

- Design changes that alter the operating principle of the product, such as changing the test method from immunofluorescence to ELISA or from a photometric to a chromatographic measurement

- Any change that adversely affects the performance of the product. That is, any non-significant changes described must be evaluated to determine if they adversely affect performance and thereby become a significant change, if applicable

- Non-significant

- Changes that affect software

- Non-significant

- Bug fixes (again, the impact on security and performance must be reviewed)

- Updates to existing runtime environments, such as Windows updates

- User interface improvements

- Significant

- Changes in the runtime environment, such as a change of operating system

- Modifications to the software architecture or algorithm

- Implementation of an algorithm that serves as a control loop and replaces user input

- Non-significant

- Material changes as well as modifications of the sterilization process

- Non-significant

- Changes related to materials that are not significant to the operating principle, such as the substitution of a preservative or replacement of chemicals for REACH compliance (if there is no degradation of performance)

- Modification of sterilization cycle parameters as part of a certified QMS

- Significant

- Changes in ingredients and materials essential to the principle of operation, such as PCR primers, antibodies or antigens in immunoassays, or markers in chromatography

- Change in sterilization method, which specifically includes changing a non-sterile product to a sterile one

- Packaging changes that may adversely affect the assurance of sterility

- Non-significant

c) FAQ of the CAMD

In its FAQ, CAMD (Competent Authorities or Medical Devices) also addresses the question of when a design change is "significant." However, the answer to question 17 does not contain anything really new compared to the MDCG document.

d) Special case software

This chapter summarizes the regulatory requirements and guidance for software and essentially goes along with the examples of MDCG 2020-3 and MDCG 2022-6.

Significant software changes

A design change would likely be significant for software if any of the following conditions exist:

- There is a change to the intended use, including

- intended use environment

- intended user groups

- new or different indications

- fewer contraindications (i.e., an expansion of the intended use)

- You eliminate a bug in the software or associated instructions for use to minimize risks (> recall)

- You change the user-product interface (minor changes such as correction of spelling errors excluded). This is especially true if you

- Add, change, or remove warning messages

- Add new security-related use scenarios

- Change critical UI elements (formerly main operating functions)

- You use a new technology, e.g., a new framework, new SOUPs (not meaning a new version), or even a different programming language

- The software is to be used for in a different runtime environment (operating system or version, processor, screen size/resolution)

- The software has to serve a new data interface

- The developers add new tables or foreign relationships in the database

- The developers change a central algorithm or replace user input with an algorithm that serves as a control loop, e.g., for calculating drug doses, for radiation planning, or for image processing

- This concerns, in particular, the replacement of conventional algorithms by AI algorithms or the replacement of an AI model (e.g., neural network by a boosting procedure)

Non-significant software changes

Typically, one does not count the following changes to the software as reportable:

- Bug fixes (again, the impact on security and performance must be verified)

- User interface improvements

- Security patches and updates to existing runtime environments, such as Windows updates

- Update of a SOUP with a newer version

- Small refactorings, e.g., within a method

- Adding an attribute to a database or changing the data type of an attribute

- Adaptation of the software to work with new versions of an existing interface specification (e.g., update from HL7 V2.7 to 2.8)

- Small measures to improve non-functional properties such as robustness (e.g., additional value checking)

4. Summary and conclusion

For many manufacturers, it is very confusing that there are basically three levels of consideration for product changes, which are described in this article:

- Design Changes as such, with the corresponding process and documentation requirements

- The decision on which of the changes have to be communicated to the notified body

- In case there is still a valid declaration of conformity against the MDD/IVDD directives: The decision from when the declaration of conformity expires due to a product change.

Unfortunately, the terms "significant change" and "substantial change" are used simultaneously for the last two change criteria.

In case of doubt, the Johner Institute recommends making a clear agreement with the notified body.

To a limited extent, our free micro-consulting is available to manufacturers, authorities, and notified bodies for such assessments.

The distinction in the MDR and IVDR between software changes that require a change to the UDI-DI and those that "only" result in a change to the UDI-PI may be useful in distinguishing between reportable and non-reportable changes: a change to the UDI-PI is usually not reportable.

MDCG's 2020-3 and 2022-6 documents provide good guidance for distinguishing between significant and non-significant design changes in the context of the validity of declarations of compliance during the transition to regulations. With the revised 2020-3 for medical devices under MDR and the 2022-6 for IVDs, mature guidance is available that includes specific examples of changes.