The FDA eSTAR Program: should or must you take part?

With the eSTAR Program, the FDA aims to increase the efficiency of approval procedures (e.g. the 510(k) procedure) through digitalization.

This article tells you how forward-looking this approach is and whether you should or even must take part.

1. What is the eSTAR Program?

The eSTAR Program enables medical device manufacturers to submit their approval documents to the FDA via an interactive PDF template.

a) Interactivity

Here interactive means:

- integrated error checking

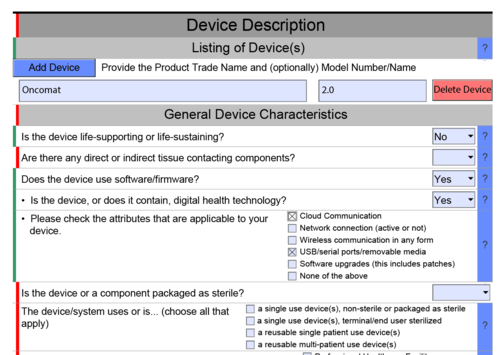

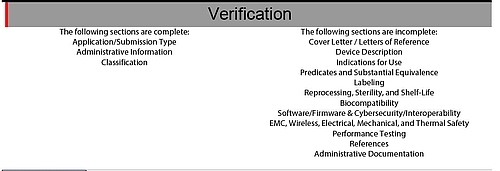

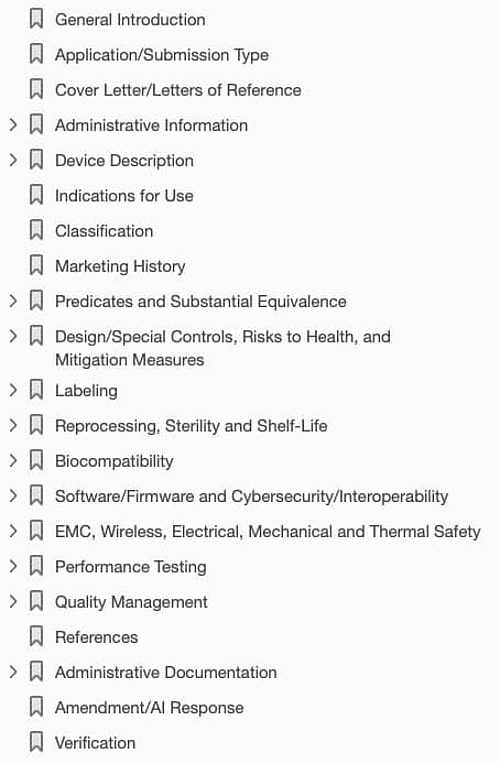

The PDF highlights areas that obviously still contain erroneous data in red and correct areas in green (see Fig. 1) - areas are displayed/hidden automatically

The interactive document displays or hides areas depending on the selection. For example, the document shows details on software documents when it is confirmed that the product contains software or is a standalone software (see Fig. 1). - integration of attachments

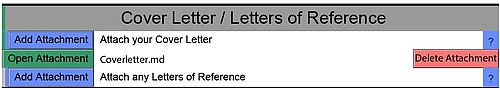

The PDF enables attachments to be included. From the FDA’s point of view, such attachments must be included. There are no restrictions as far as the data format is concerned but the size of the resulting PDF document is limited to 1 GB (see Fig. 2). - possibility to import and export

With the exception of attachments, all data can be imported from XML via the PDF and exported to XML.

b) Submission on physical data carriers

After filling out the template, however, manufacturers find that this digitalization has its limits:

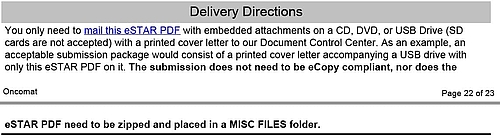

You only need to mail this eSTAR PDF with embedded attachments on a CD, DVD, or USB Drive (SD cards are not accepted) with a printed cover letter to our Document Control Center.

However, since July 2022 the FDA has provided the option of uploading eSTAR and eCopy submissions electronically via the Customer Collaboration Portal (CCP). At present, this option is in the trial phase and is only offered to existing CCP users. Nevertheless, we can assume that the FDA will soon be switching to electronic submission to the delight of many manufacturers.

c) eSTAR versus the eCopy program

After the eCopy/eSubmitter program, the eSTAR Program is the next step on the digitalization ladder. In the case of the eCopy/eSubmitter program, the FDA “only” specified the formatting of the electronic documents submitted, which manufacturers had to adhere to. With the eCopy/eSubmitter program there is no default document structure or structured data as in the case of the eSTAR Program.

Further information

If you would like to know more about the background of these two programs and see a comparison, we recommend you take a look at this guidance document.

2. Who can or should use the eSTAR Program?

The eSTAR Program is obviously aimed at helping medical device manufacturers to compile and submit their approval documents faster and to a higher quality. But it is not aimed at all manufacturers and is not suitable for all approval procedures.

The eSTAR Program is only applicable to

- 510(k) approval procedures (traditional, abbreviated, special)

- De Novo approval procedures

- medical devices and IVDs.

However, it is not applicable to

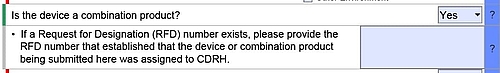

- combination products

The FDA explicitly states: “The eSTAR is not currently for use with combination products.” So combination products are ruled out. Interestingly, the interactive PDF enables you to select combination products as a product type (see Fig. 4). - the PMA approval procedure

This certainly does appear to be envisaged, or at least the PDF includes this option, even if it is still greyed out at present.

Please note!

Participation in the eSTAR Program is entirely voluntary. This means that manufacturers and products to whom the procedure is applicable can but do not have to take part. The program is not open to anybody else.

How does the eSTAR Program help?

The eSTAR Program is beneficial both to manufacturers and the FDA.

Higher-quality documents

The FDA receives the documents in a higher quality as the PDF helps manufacturers to avoid blatant errors such as missing information or typos (e.g. in product codes). The drop-down lists and simple content checks for completeness and consistency are helpful.

Greater reliability

The PDF verifies and highlights incomplete or missing information both in terms of individual pieces of data and the document as a whole (see Fig. 5).

Time saving

Manufacturers and the FDA save themselves from going through the RTA correction loop. However, the rest of the process remains unchanged:

The remainder of a 510(k) review will be conducted according to the FDA guidance, “The 510(k) Program: Evaluating Substantial Equivalence in Premarket Notifications [510(k)],” following the procedures identified in 21 CFR 807 subpart E. A De Novo review will be conducted according to the FDA guidance, “De Novo Classification Process (Evaluation of Automatic Class III Designation),” following the procedures identified in 21 CFR 860, subpart D.

The FDA does not have to transfer any contents into its own system by copying and pasting. This also saves time and effort.

Furthermore, the FDA can find the documents faster as contents and attachments can be directly accessed in the same place via the PDF document and because manufacturers are obliged to share attachments in the exact format specified by the FDA. This also saves work. However, it does not promise shorter processing times.

Conclusion

Summary

With the eSTAR Program the FDA has taken the next step toward digitalizing the approval process. It is taking to extremes what can be achieved with a document and PDF-based approach.

The interactivity of the PDF documents with integrated application logic and a combination of structured data and attachments gives us an idea of what is possible with fully-automated collection and verification of approval data.

Until then, manufacturers have to work with documents and observe the following guidance documents:

- the existing guidance document “Providing Regulatory Submissions for Medical Devices in Electronic Format — Submissions Under Section 745A(b) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act”, even if it is not totally up to date as it was published before the eSTAR Program and does not yet include the program

- more importantly, the newer guidance document “Electronic Submission Template for Medical Device 510(k) Submissions”

Pros

With this program the FDA helps manufacturers to compile better, complete, consistent and correct documents. The FDA itself benefits from this as thanks to the software many preliminary verifications are automated.

This in turn is beneficial to manufacturers as approval processes are faster and, more importantly, unnecessary correction loops (incl. the RTA review) can be avoided.

The structure of the PDF document and the sharing of attachments encourages manufacturers to structure their own documents, both in terms of the documents as a whole and their index as well as the contents of the documents.

Cons

The possibility of an XML import can in the best-case scenario be a bridging solution for transferring information from existing systems into the FDA’s PDF document. Although it is better than manual copying and pasting, it is no match for an API.

The FDA specifies the required attachments. This obliges manufacturers to compile FDA-specific documents which in turn leads to the usual painstaking administrative tasks of Regulatory Affairs managers; tasks that full digitalization of the processes could and should render superfluous.

In addition, the PDF may contain errors. In our case, we were not able to enter data in the “Quality Management” section even though it appears in the index (see Fig. 6). Furthermore, the guidance document does not explain this section.

What appears to be quite absurd in the context of digitalization is the obligation to submit the electronic document on a physical data carrier. However, a test phase for electronic submission via upload has started.

Appraisal and outlook

Thanks to the eSTAR Program, the FDA is clearly a step ahead of many notified bodies and their application forms. Often the latter can neither keep up with functionality nor usability and interoperability (XML import and export).

The interactive PDF is also software that, like all other software, needs to be validated and further developed. For example, the eSTAR Program software still classifies according to levels of concern, whereas the current version of the guidance document on software already differentiates between basic documentation and enhanced documentation. As a result, it is not possible for manufacturers to follow the newer (and better) version of the new guidance document.

Furthermore, this example shows that the eSTAR Program (as is typical of software) greatly restricts the degree of freedom with all of the advantages and disadvantages that this entails.

Comparison with our digital approval platform

The eSTAR Program is a step in the right direction but at the same time it will entrench this incomplete level of digitalization for years to come.

It would have been preferable for the FDA to have achieved the same level of digitalization as the Johner Institute’s digital approval platform:

- (largely) complete collection and verification of structured data rather than attachments and text boxes that cannot be analyzed by a computer. eSTAR uses a single text box for the whole intended purpose including characterization of users and patients

- (almost) document-free submission

- largely complete automated verification of all data

- complete access to all data via API and thus integration into the manufacturer’s and authority’s or notified body's existing systems

- no media disruptions and in particular no need to transfer information on documents (paper, PDF) or submit it using physical data carriers

- support is provided throughout the process until approval is successful or declined, including feedback from the authority or notified body