State of the Art: It’s Worse Than You Think

Auditors and regulatory authorities regularly discuss what the state of the art is with medical device manufacturers. These discussions are intensifying in the light of the new EU regulations.

Manufacturers are threatened with delays to authorizations, unnecessary re-designs of devices, and costly clinical investigations or, for in vitro diagnostic devices (IVDs), clinical performance studies.

1. Why is it so difficult to define the state of the art?

Almost all manufacturers are committed to meeting the regulatory requirements and developing devices according to the “state of the art.” Unfortunately, there are a lot of hurdles in their way:

a) No harmonized standards

There will be no harmonized standards for the MDR and IVDR for the foreseeable future. In the past, these harmonized standards usually formed a good consensus between manufacturers on one side and authorities and authorities or notified bodies on the other.

b) No definition of the term

Although the two regulations both use the term “state of the art” over 20 times, and require this state of the art, they do not define the term.

Anyone hoping to find clarity in other sources will end up with additional questions as to what the state of the science is and how it differs from the state of the art.

c) Inconsistent use of the term

As if the absence of a definition wasn’t bad enough, the regulations also contain different versions of the term. There isn’t just

- the “state of the art”, there's also

- the “latest state of the art”

- the “generally acknowledged state of the art” and

- the “current state of the art.”

d) Incorrect and inconsistent translations

Even those who think they can differentiate between these variations will surely feel overwhelmed by the time they compare the German and English versions of the regulations. For example, the English version of the clinical evaluation plan requires: “taking into account the state of the art”. The performance evaluation plan for IVDs must contain a “description of the state of the art.” In the German versions of the MDR and IVDR, the corresponding parts of the text state that the “neueste Stand der Technik” [latest state of the art] has to be taken into account.

The German version demands the “neusten Erkenntnisstand” [latest state of knowledge] and the “neusten medizinischen Kenntnisstand” [latest state of medical knowledge], whereas the English version always refers to the “state of the art”.

These discrepancies are not(!) isolated cases.

e) Notified bodies have not provided any clear statements

Even when expressly asked, German notified bodies could not or were not allowed to make a clear statement on whether manufacturers should reference standards when having their devices authorized, and if so which standards and versions should they reference:

- Standards harmonized under the directives

- Standards planned for harmonization under the MDR/IVDR

- The latest version of the standards

Conclusion

Manufacturers have to develop their devices taking into account the state of the art and the devices must comply with the state of the art. Unfortunately, manufacturers are pretty much left to the own devices when it comes to the question of what the state of the art is and how it is defined.

2. “State of the art” versus “state of the science”

a) Preliminary note

There is no universally accepted and industry-independent definition of the two terms. The following information is, therefore, limited to the domain of medical devices and IVDs.

b) Definition in ISO 14971:2019

The third edition of ISO 14971 adds the missing definition of the term “state of the art”:

developed stage of technical capability at a given time as regards products, processes and services, based on the relevant consolidated findings of science, technology, and experience

ISO 14971:2019

The standard adds the following note to the definition:

The state of the art embodies what is currently and generally accepted as good practice in technology and medicine. The state of the art does not necessarily imply the most technologically advanced solution. The state of the art described here is sometimes referred to as the “generally acknowledged state of the art”.

ISO 14971:2019

This note is very helpful for manufacturers:

- Manufacturers can equate the “state of the art” and the “generally acknowledged state of the art” and thus avoid unnecessary discussions about the differences between the two.

- The most “technically advanced solution” is not demanded.

c) Product life cycle and classification

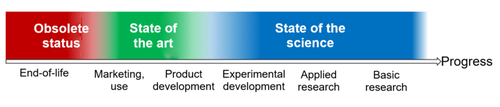

There are several phases in the development of products and technologies (source):

Phase | Activity, aim | Typical actors | Example |

Basic research | Generating new knowledge without any specific aim in terms of a product | Universities, large-scale research | Image recognition with machine learning (ML) |

Applied research | Generating new knowledge to enable the development of improved or new components, products, or processes | Universities, colleges | Transfer of these methods to oncology |

Experimental development | Combining the results of applied research and existing (proven) technologies in order to minimize development risks, i.e. to find out how specific products and procedures can be designed and developed | Manufacturer, development service provider | Development of an MVP |

Product development | Developing or refining a specific medical device so that it can be authorized and to be successful in the market | Manufacturer, development service provider | Development of the specific device in compliance with the MDR or IVDR |

Table 1: Phases from research to the developed product

These products are marketed, refined, and withdrawn from the market at the end of the product life cycle.

According to ISO 14971, the state of the art is the generally accepted good practice in technology and medicine and not necessarily to the most technically advanced solution. The most technically advanced solution is the one that marks the boundary between the state of the science and the state of the art. Whether the MDR and IVDR are referring to this boundary when they talk about the “latest state of the art” is not clear.

c) Example

The following example illustrates the differences:

State | Encryption |

State of the science | Quantum cryptography |

State of the art | BSI recommendations and key lengths (e.g. according to BSI TR-02102-1) |

Obsolete | WEP encryption of WLANs |

Table 2: Examples of the state of the science, the state of the art and an obsolete status

d) Problems

Unfortunately, a lot of regulations do not distinguish precisely between the state of the art and the state of the science. For example, MEDDEV 2.7/1 sometimes seems to equate the “state of the art” and “current knowledge.” But the latter corresponds more to the published state of the science.

3. Regulatory requirements for the “state of the art”

a) Aims of the regulations

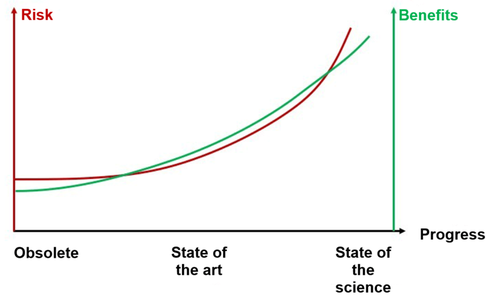

The regulations attempt to ensure that the devices provide the highest level of benefits and safety. Newer devices often offer greater benefits. But since their technologies are not as tried and tested, the benefit-risk ratio is not necessarily better.

The regulations also aim to ensure that the requirements for the devices are not so high that manufacturers can no longer economically viably comply with them, since devices that would have an excellent benefit-risk ratio but that never reach the market do not provide any benefits at all.

Whether the authors of the regulations really see this second aspect as an aim sometimes seems questionable.

b) MDR and IVDR requirements

The MDR and the IVDR demand the state of the art in the following areas, among others:

- Definition of the performance requirements (MDR Annex I.1. and IVDR Annex I.9.1)

- Determination of the benefit-risk ratio and risk acceptance (MDR and IVDR Annex I.1. )

- Selection of risk-minimizing measures (MDR and IVDR Annex I.4)

- Software development (MDR Annex I.17.2 and IVDR Annex I.16.2)

- Planning and conduct of clinical evaluations, or performance evaluations of IVDs (MDR Annex IX.2.1 and IVDR Annex XIII.1)

- Performance of clinical investigations (MDR Annex XV, Chapter II.3) or clinical performance studies for IVD devices (IVDR Annex XIII.2.3.2)

The IVDR also demands the state of the art for the:

- Planning of post-market performance follow up (PMPF) (Annex XIII.5.2)

- Scientific advice from EU reference laboratories (Article 100)

c) MEDDEV 2.7/1

Very similar requirements are set out in the guideline for clinical evaluations, MEDDEV 2.7/1 rev. 4. It also requires manufacturers to determine the state of the art and take it into account when:

- Defining the benefit-risk ratio

- Updating the clinical evaluation

- Determining the clinical performance and the clinical safety profile

- Carrying out literature search

Benefits and risks should be specified, e.g. as to their nature, probability, extent, duration, and frequency. Core issues are the proper determination of the benefit/risk profile in the intended target groups and medical indications, and demonstration of acceptability of that profile based on current knowledge/ the state of the art in the medical fields concerned.

When updating the clinical evaluation, the evaluators should verify: compatible with a high level of protection of health and safety and acceptable according to current knowledge/ the state of the art;

Sufficient detail of the clinical background is needed so that the state of the art can be accurately characterised in terms of clinical performance, and clinical safety profile.

Brief summary and justification of the literature search strategy applied for retrieval of information on current knowledge/ the state of the art, including sources used, search questions, search terms, selection criteria applied to the output of the search, quality control measures, results, number and type of literature found to be pertinent. Appraisal criteria used.

Applicable standards and guidance documents.

MEDDEV 2.7/1 rev. 4

4. Defining the state of the art

a) Step 1: preliminary considerations, identifying initial criteria

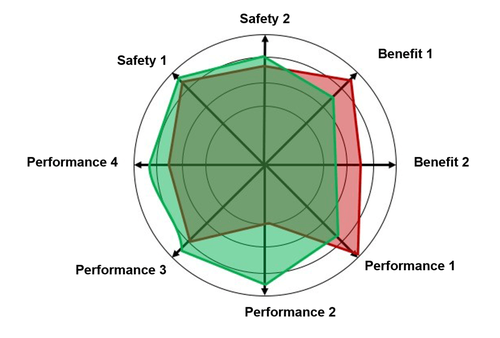

Manufacturers have to define the state of the art.

Careful!

Please note: THE state of the art for a device does not exist! Rather, the state of the art of various aspects in the categories clinical benefit, safety and performance has to be determined. See Fig. 3.

b) Step 2: compiling key questions

Manufacturers should consider the key questions they can use to determine the state of the art. These key questions can be divided into two groups:

Alternatives:

- What are the alternative devices, e.g. predecessor devices and competing devices? For IVDs: Are reference methods available and, if so, what are they?

- Do alternative device categories exist? For example, MRI instead of CT scans

- Are there alternative procedures or, in the case of IVDs, alternative diagnosis options? For example, chemotherapy instead of radiotherapy, qPCR instead of pathogen culture, manual image evaluation instead of ML-supported evaluation

- What alternative materials and technologies are available?

- What are the alternatives in terms of other device designs?

- Are there other production processes?

Comparison of the alternatives:

- How do these alternatives compare in terms of clinical benefit? For example:

- Sensitivity and specificity of a diagnosis

- Number of days in hospital

- Percentage of cured patients

- Reduction of the pain level on a 10-step scale

- Possibility of diagnosing different clinical subpopulations

- How do these alternatives compare in terms of performance? For example:

- Lifetime of an implant

- Accuracy of the RF pulse generation

- Number of possible reprocessing cycles

- Resolution of an imaging procedure

- Limit of detection of a diagnostic analysis method

- Time until the diagnosis is available

- How do these alternatives compare in terms of safety?

- Mean time between failure

- Protection against incorrect entries and other use errors

- Probability of air bubbles being detected in an infusion line

- Stability when the device is dropped

c) Step 3: searching sources

Guidelines such as MEDDEV 2.7/1 even name specific sources of information. The following sources are recommended for manufacturers:

- Regulatory authority databases, e.g., SwissMedic, BfArM, FDA

- Clinical literature, e.g., via PubMed and Embase

- Registers

- Trade fair and product catalogs, instructions for use

- Technical databases, e.g., on material properties

- Standards, regulatory guidance documents

- Medical guidelines from professional societies

- Information from manufacturers about faults, e.g., bug reports and release notes

- Some post-market data, e.g., customer complaints, service reports, post-market clinical follow up, or post-market performance follow up for IVDs, log files

- Lab tests

d) Step 4: analyzing sources

First of all, manufacturers need to look at each aspect of the key questions individually. At the end of the end of this analysis, they should be able to answer the following questions:

- Is there any information that would allow conclusions to be drawn about this aspect?

- What alternative devices, technologies, procedures, etc. exist?

- Which of them are better, which are worse?

- Does this information represent the state of the art or the state of the science?

Normally, the development of standards and guidelines takes several years. Therefore, they represent the state of the art rather than the state of the science.

This analysis can now be used as the input for, for example:

- The clinical evaluation/performance evaluation

- The risk management file

- Development

- The post-market surveillance plan

NB!

Make sure that the alternative procedures, devices, and technologies really are comparable. Comparability also takes into account the patient population, the indications and contraindications, the intended users and the intended use environment.

e) Step 5: repeating the analysis periodically

What is the state of the science today may soon be the state of the art and obsolete not long after. For example, with machine learning methods, this cycle sometimes lasts only a few months.

That's why the regulations require manufacturers to update their analysis at regular intervals. For example, during the post-market clinical follow up (PMCF) or, for IVDs, the post-market performance follow up (PMPF). In most cases, the cycle should not be longer than one year.

5. Conclusion and summary

a) Difficulties and possible solutions

The EU regulations make it unnecessarily difficult for manufacturers to meet the central requirements of these very regulations due to the absence of a definition of the term, the inconsistent use of the term “state of the art” and annoying translation errors.

The third edition of ISO 14971 provides an urgently needed definition. The fact that this standard is not intended for harmonization and so does not itself represent the state of the art (?!?) is the perfect irony.

b) Aspects that make up the state of the art

Manufacturers should consider the following variants of the term to be synonyms:

- State of the art

- Generally acknowledged state of the art

- Latest state of the art

ISO 14971 makes these simplifications possible.

The search for alternative devices, procedures and technologies is an essential part of this. Manufacturers have to compare and evaluate these alternatives with regard to safety, performance, and clinical benefit.

The statement that a device meets the state of the art is justified if it applies for all the relevant aspects such as benefit, performance (e.g., “essential performance characteristics”) and safety.

However, this also means that, if an alternative device is superior to a device in one aspect, the manufacturer of this second device does not necessarily have to follow suit. This evaluation has to consider all the aspects that make up the state of the art.

c) Role of standards

In the case of older standards, manufacturers will find it increasingly difficult to argue that they represent the state of the art. This is also true for the most recent editions.

Even the most recent standards do not claim to reflect the state of the art.

Unfortunately, the notified bodies have not yet been moved to make a clear statement as to whether standards can, or must, be used to define the state of the art, and if so which ones.

d) A continuous process

The state of the art is not a constant. Manufacturers are obliged to define the state of the art continually, usually at least annually. Manufacturers can fulfill this obligation as part of their post-market surveillance or post-market performance follow ups (for IVDs).

If you are not sure whether your device complies with the state of the art and will pass the next audit without any problems, then please get in touch with us, e.g. through our free micro-consulting service.

The Johner Institute can help you automatically monitor the state of the art using our Post-Market Radar.