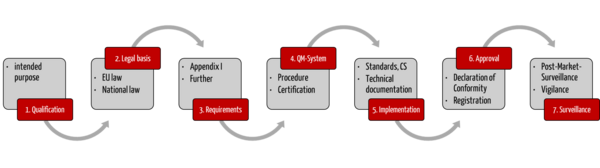

In 7 steps to a medical device

Anytime you want to launch a medical device on the market, you quickly come to the question of which legal regulations you have to comply with.

This article will give you answers and present the seven steps to quickly place your devices on the market in compliance with the law.

Step 1: Determine if the product is a medical device or IVD

The first question you should ask yourself is: is your product actually a medical device at all? This decision is called qualification.

If the device is not a medical device, other or even no regulations apply to it.

The intended purpose is the key to answering the question “medical device, yes or no?”

The manufacturer determines the intended use of the device. It is irrelevant what else the device could be used for or what other features it provides.

a) Medical device as defined in the MDR

If the device is used for medical purposes as defined by the Medical Device Regulation 2017/745 (MDR), it is a medical device. The MDR defines what a medical device is:

Definition of “medical device”

‘medical device’ means any instrument, apparatus, appliance, software, implant, reagent, material or other article intended by the manufacturer to be used, alone or in combination, for human beings for one or more of the following specific medical purposes:

- diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, prediction, prognosis, treatment or alleviation of disease,

- diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, alleviation of, or compensation for, an injury or disability,

- investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy or of a physiological or pathological process or state,

- providing information by means of in vitro examination of specimens derived from the human body, including organ, blood and tissue donations,

The following products shall also be deemed to be medical devices:

- devices for the control or support of conception;

- products specifically intended for the cleaning, disinfection or sterilisation of devices as referred to in Article 1(4) and of those referred to in the first paragraph of this point.”

Source: MDR Article 2

Example: heart rate tracker software

- When used for fitness purposes (e.g., in a smartwatch), the analysis software is not a medical device.

- However, if the intended purpose is to use the data from the software to diagnose or monitor a disease, the analyzing software is a medical device.

b) In vitro diagnostic medical device according to IVDR

The product could also be an in vitro diagnostic medical device (IVD). IVDs are medical devices and fall under the corresponding legal regulations.

Classification as an IVD is also based on the intended purpose, as the definition from Art. 2 of the IVDR makes clear:

Definition: “IVD”

“‘In vitro diagnostic medical device’ means any medical device which is a reagent, reagent product, calibrator, control material, kit, instrument, apparatus, piece of equipment, software or system, whether used alone or in combination, intended by the manufacturer to be used in vitro for the examination of specimens, including blood and tissue donations, derived from the human body, solely or principally for the purpose of providing information on one or more of the following:

(a) concerning a physiological or pathological process or state;

(b) concerning congenital physical or mental impairments;

(c) concerning the predisposition to a medical condition or a disease;

(d) to determine the safety and compatibility with potential recipients;

(e) to predict treatment response or reactions;

(f) to define or monitoring therapeutic measures.

Specimen receptacles shall also be deemed to be in vitro diagnostic medical devices;”

Source: Article 2 IVDR

The intended purpose ultimately also determines the risk class of a medical device. This risk class in turn determines, among other things, which conformity assessment procedure the device has to go through (see below).

There are special requirements for accessories or software, which we discuss in a separate article.

Step 2: Identify relevant legal regulations

a) The role of EU regulations and directives

European law is above German law in the legal hierarchy. This means that you must give priority to binding European law.

EU regulations are directly binding for manufacturers and individuals. So, you have to differentiate these from EU directives that do not apply directly to you.

Further information on EU regulations and EU directives:

EU regulations are directly binding EU legal acts. They do NOT have to be implemented by member states to be effective.

This means regulations function like “European laws.” Manufacturers must, therefore, give priority to EU regulations over German law. (e.g., the german Medical Device Implementation Act - MPDG). The laws may only supplement and concretize the EU regulations.

EU directives: In contrast, directives issued by the EU are only binding for the member states. In order for them to be also binding for citizens and companies, they have to be transposed into national law. Manufacturers should therefore be primarily guided by the German law that implements the directive (e.g., the German Medizinproduktegesetz (MPG)), not the directive itself.

This distinction is crucial because national legislators have a margin of appreciation when it comes to implementing a directive. In fact, a lot of national laws go beyond the requirements of the directives.

Regulations relevant for medical devices

The most important EU regulations for manufacturers are:

- Regulation 2017/745 on medical devices (MDR) (binding)

- Regulation 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDR) (binding)

Other regulations may apply if the manufacturers act as economic operators or according to the product portfolio:

- Regulation (EU) 2012/207 - Regulation on electronic instructions for use of medical devices (binding, already partially repealed, final repeal as of May 2024)

- Regulation (EU) 2016/679 - Regulation on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (binding)

EU directives continue to exist for some topics, e.g.:

- Machinery Directive 2006/42/EC (if the medical device contains moving parts)

- RoHS 2011/65 (EU) - Directive on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment (this directive is subject to ongoing amendments by delegated directives. These are issued by the EU Commission to amend existing regulations. There is more information on these on the EU's web pages.)

b) National law

In addition to European law, manufacturers have to consider national law. This is particularly relevant if the national law:

- establishes completely independent regulations,

- implements European directives or

- adds to European regulations.

German law, like EU law, also has varying degrees of “force.” It consists of:

- Laws

- Example: Medizinprodukterecht-Durchführungsgesetz (MPDG) (German)

- Ordinances

- Example: Medizinprodukte-Anwendermelde- und Informationsverordnung (MPAIMV)(German)

- Example:Medizinprodukte-Betreiberverordnung (MPBetreibV)(German)

- Other guidelines

- Example:Technical Guidelines(German) from the German Federal Office for Information Security (BSI).

Step 3: Define the regulatory requirements

Once you have determined which regulations apply to your device, you have to identify the requirements they impose. As a rule, these involve:

a) Classifying the device

The conformity assessment procedure for your device depends on its risk class. The conformity assessment procedure is the procedure for demonstrating that your device complies with the relevant legal requirements.

- The MDR has risk classes I to III.

- The IVDR has risk classes A to D.

There are stricter requirements for devices with high risk classes than for those with lower risk classes.

The rules for the classification of your device can be found in Annex VIII of the MDR or Annex VIII of the IVDR. You should also refer to the corresponding guidance documents.

Furhter information

You can read more on the classification according to the MDR in our article Classification of Medical Devices.

You can read more on the classification of IVDs in the article Classification of In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices: How to Avoid Over-Classification.

The risk class determines the conformity assessment procedure.

b) Selecting the conformity assessment procedure

The conformity assessment procedure steps differ according to the risk class:

c) The quality management system

If you place medical devices on the market, you need to have a quality management system (QMS). The minimum requirements can be found chiefly in the MDR/IVDR.

There is, however, one peculiarity: For class I/class A devices, the QM system does not have to be certified by a notified body, but in all other cases, it does

Further information

Find more information on the topic of the QM system in our QM Systems & ISO 13485 overview.

You can see what a QM SOP instruction should look like in our article Creating Standard Operating Procedures for QM.

Step 4: Establish a QM system

If you place medical devices on the market, you need to have a quality management system (QMS). The minimum requirements can be found in Articles 10 of the MDR and IVDR, respectively, and in their Annexes IX.

For Class I devices or Class A IVDs, the QM system does not need to be certified by a notified body, but in other cases, it usually does:

According to Annex XI, the most commonly used conformity assessment procedure for class IIa and higher devices requires a certified QM system. Other conformity assessment procedures, such as that according to Annex XI Part B, are only helpful in a few cases.

Step 5: Comply with the regulatory requirements

Once you have identified which legal requirements apply for your device and your organization, you have to meet these requirements (and demonstrate that you have done so). You can use, among other things, standards to help with this.

a) Standards

Medical device manufacturers can use standards to demonstrate that their device meets the requirements of the legal regulations. Standards represent the state of the art. Their application is voluntary. But because they are often widely recognized, they make it easier to demonstrate conformity due to standardization and their consistent application.

Standards are produced by independent (non-governmental) standards organizations. The name of each standard is preceded by an abbreviation to indicate which organization developed the standard.

Overview of the most important standards organizations with abbreviations

- DIN

- Deutsches Institut für Normung (EN: German Institute for Standardization, registered association based in Berlin)

- EN

- European standards organizations Comité Européen de Normalisation (CEN; EN.: European Committee for Standardization), Comité Européen de Normalisation Electrotechnique (CENELEC; EN.: European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization)

- CEN: Standards for European standardization in technical fields

- CENELEC: Standards for European standardization in electrotechnical fields

- ETSI

- European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI)

- Private, non-profit organization for European standards in the field of information and communication technology

- ISO

- International Organization for Standardization

- Standards in all areas not covered by the IEC or the ITU

- IEC

- International Electrotechnical Commission

- Electrotechnical/electronics field

- IEEE

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

- Standards mainly in the fields of electrotechnology and information technology

- ITU

- International Telecommunication Union

- Telecommunications field

Harmonized standards

Harmonized standards are aligned with European specifications and recognized by public bodies. Therefore, if manufacturers comply with these standards, there is a presumption of conformity with the requirements of EU specifications.

Further information

You can find more information in our article Harmonized Standards: Provision of Evidence for Medical Device Manufacturers

How do you find the appropriate standard?

Which standard you need depends mostly on the device.

- Identify which requirements your device has to comply with

(e.g., check Annex I of the MDR/IVDR, common specifications, any other regulations; see Step 2). - Check whether there is a standard for the requirement. If there are harmonized standards, you should prioritize these.

The following standards are good starting points for your research:

- ISO EN 13485: Medical devices — Quality management systems — Requirements for regulatory purposes

- ISO EN 14971: Application of risk management to medical devices

- IEC EN 62366-1: Application of usability engineering to medical devices

- IEC EN 62304: Medical device software — Software life cycle processes

- IEC EN 60601-1: Programmable electrical medical systems: basic safety and essential performance characteristics

- DIN EN ISO 10993-1: Biological evaluation of medical devices: Evaluation and testing within a risk management process

b) Other "evidence management tools"

Common specifications

For some MDR/IVDR requirements, there are no harmonized standards that manufacturers can use. This is where the “common specifications” established and published by the EU Commission come into play.

The MDR and IVDR define common specifications as follows:

"‘common specifications’ [...] means a set of technical and/or clinical requirements, other than a standard, that provides a means of complying with the legal obligations applicable to a device, process or system.”

Further information

You can find out more about "common specifications" in our article Common Specifications: Competition for Standards?

Guidelines and further sources

Many sources are not legally binding. However, they can help, for example, with the interpretation of laws, regulations or standards. These additional sources include:

- IMDRF documents

Documents from the International Medical Device Regulators Forum - Manual V1.22 on borderline and classification:

Manual on Borderline and Classification in the Community. Regulatory Framework for Medical Devices - MDCG documents

Not legally binding implementation and decision guidance for the MDR and IVDR. However, these documents are usually taken into account by notified bodies.

In addition, some specifications refer to the superseded EU medical device directives, some of which no longer represent the state of the art but are still relevant, at least in the transition phase.

- MEDDEVdocuments: Not legally binding implementation and decision guidance for the MDD. Find out more in our article on MEDDEV.

- NB-Med/Team NB documents: NB-Med (Association of Notified Bodies) documents. 2013/172/EU Commission Recommendation of 5 April 2013 on a common framework for a unique device identification system of medical devices in the Union

- ZLG documents: Answers and decisions from the Notified Bodies’ Experience Exchange Group

- EK-Med documents: ZLG subgroup

c) Provide general safety and performance evidence

Now that you know which standards and regulations apply to you, you need to implement them accordingly. This means:

- Either translating the requirements into a process and establishing this process in your company (e.g., software life cycle processes according to IEC 62304). You need to create SOPs and corresponding specification documents for this.

- And/or designing and developing the device so that it meets the requirements (e.g., creepage distance specifications according to IEC 60601-1). You can demonstrate this with appropriate tests.

Example: Proving usability

As a manufacturer, you must ensure the usability of your device. The usability evaluation ensures that the respective device can be used safely by the intended users in the intended use environment for the intended purpose and that no unacceptable risks arise in the course of use.

A final summative study is usually required for objective evidence of safe use.

d) Perform clinical evaluation

The clinical evaluation (performance evaluation for IVDs) is the part of the technical documentation where all the knowledge about the device is brought together. It is used to verify the safety and performance (including the clinical benefit) of the device when used as intended by the manufacturer.

If necessary, the clinical evaluation has to be supplemented by a clinical investigation. In clinical investigations, the required clinical data are generated through supervised use of the device in humans. For the IVD performance evaluation, the equivalent would be a clinical performance study.

Further information

The articles Medical Device Clinical Investigations: The 7 Biggest Challenges and, for IVDs, In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Device Performance Evaluations: 8 Steps to Conformity explain when such clinical investigations are required.

e) Assign UDI

Don't forget to assign the Unique Device Identification (UDI). This identification number makes it easy to identify and track medical devices.

Further information

Read more about the mandatory UDI system in the article Unique Device Identification (UDI).

f) Merge evidence in the technical documentation

The technical documentation consists of documents that medical device manufacturers must provide. This technical documentation is the prerequisite for the conformity assessment and thus for the authorization of medical devices.

It is regulated in Annex II of the MDR and of the IVDR.

Further information

More information on the technical documentation requirements can be found in our Technical Documentation for Medical Devices overview.

g) Further requirements and evidence

Responsible person

Both the MDR and IVDR require the designation of a Person Responsible for Regulatory Compliance (PRRC). This person must ensure the following:

- The medical devices' conformity is checked per the QM system (before delivery).

- Technical documentation and declaration of conformity are prepared and updated.

- Post-market surveillance is carried out.

- All reporting obligations are fulfilled.

- According to Annex XV, Chapter 2, a declaration is issued for investigational devices.

The appointment of the responsible person is mandatory. In case of neglect of these obligations, administrative penalties of up to 30,000 euros may be imposed in Germany.

Further information

For details on the tasks and required competencies of the responsible person, please refer to the article "MDR/IVDR - 'Person Responsible for Regulatory Compliance' (PRRC)."

Post-Market Surveillance Plan

The technical documentation also includes the plan for "monitoring after placing on the market" (post-market surveillance). More on this is described in step 7.

Step 6: Declare Conformity & 'Approve' Device

Once you have met all the requirements, there are only a few more aspects to consider before you are allowed to launch your device.

a) Declare conformity

In the declaration of conformity, a manufacturer declares that its device complies with the legal requirements.

So, after ensuring that all the requirements have been met, the manufacturer issues this declaration of conformity for its device. The necessary certificates from a notified body may be needed for this.

Furhter information

You can find out exactly what the declaration of conformity contains in our article EU Declaration of Conformity.

b) Register as a manufacturer

Manufacturers must register with the European Database on Medical Devices (EUDAMED).

Furhter information

Find out more in our article EUDAMED: European Database on Medical Devices.

c) Register the devices

In addition, manufacturers have to register their devices with the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) or via EUDAMED.

Step 7: Surveil devices on the market

Even after you have launched your device on the market, you are still responsible for its safety and performance. You should have already established processes for this in your quality management system. These processes include:

a) Post-market surveillance

Even after you have launched your device on the market, you have to surveil it.

Post-market surveillance is a proactive and systematic process for establishing corrective and preventive actions (CAPAs) from information about medical devices that have already been placed on the market.

Further information

You can find out more about post-market surveillance in our article Post-Market Surveillance and Surveillance of Devices on the Market.

b) Vigilance

Vigilance means that every “serious incident” and every safety-related corrective action has to be officially reported to the relevant authorities. Therefore, unlike post-market surveillance, vigilance is reactive, not proactive.

The reporting obligations are set out in Article 87 of the MDR and Article 82 of the IVDR.

Conclusion and summary

When launching a medical device on the market, manufacturers have to take numerous legal requirements into account. At first glance, this can seem overwhelming. However, our seven steps can act as a guide and help you get your medical device through the regulatory authorization process smoothly.

If you are still unsure or have further questions, you can contact your notified body or the Johner Institute.