Classification of in-vitro diagnostic medical devices: how to avoid too high a classification

With the introduction of EU Regulation 2017/746 on in-vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVDR), in-vitro diagnostic medical devices (IVD) are assigned to certain risk classes. This has extensive consequences: among other things, the risk class has an impact on the conformity assessment procedure, certification audits and market introduction.

In order to ensure that your IVD product is not unnecessarily allocated to too high a risk class, this article provides an overview of

- how IVDs are classified according to the new IVDR,

- how you can avoid an unnecessarily high classification, and

- how the Johner Institute’s IVD classifier tool can help you.

1. Why the right classification is important

a) IVDD is becoming IVDR: what that means for classification

In May 2022, the IVDD, the previous Directive 98/79/EC on in-vitro diagnostic medical devices, will be replaced by the IVDR. This gives the classification of IVDs a new level of importance.

Under the IVDD there was not in principle even a classification, as the EU Directive was missing a key part that would have been needed for this: there were no classes. Instead, the IVDD contained lists of critical markers.

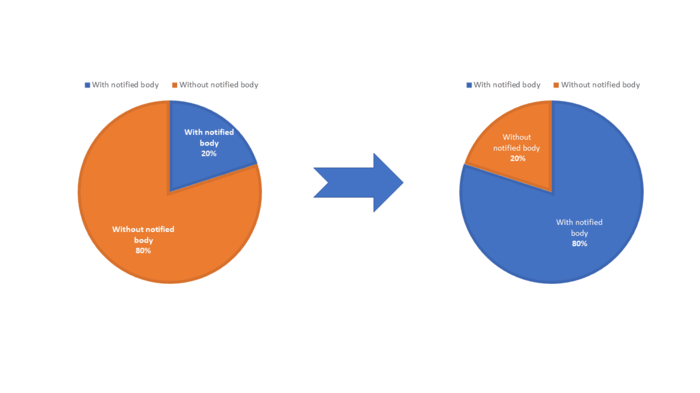

The IVDR is now introducing a rule-based classification system with risk classes A to D. Firstly this leads to significantly more monitoring by notified bodies and secondly will result in discussions in audits and when inspecting product files. Estimates indicate an increase in the level of monitoring from 20% currently to at least 80%.

Fig. 1: Significantly more IVD will be assessed by notified bodies in the future. This estimate is based on consistent statements from notified bodies and independent international specialists. It is also the Johner Institute’s opinion.

Far more products come under the future IVDR than previously came under the IVDD.

This affects in particular

- IVD software,

- What are known as companion diagnostics (CDx), and

- Products that make predictions, in other words that determine predictive values such as the risk values of a certain disease (this primarily affects genetic tests).

b) Consequences of incorrect classification

Incorrect classifications can lead to deviations in the audit and in the product inspection by the notified body. In an even less favorable scenario, an authority classifies the product in an unnecessarily high class, inevitably resulting in a delay in market introduction. Competitors can also query the classification and use actions for injunction to prevent the marketing of the products.

It is therefore critical that all parts of IVD products are classified correctly under the IVDR to prevent these problems.

You can find tips on how to do that further down in this article.

2. Classification according to the IVDR

The classification of IVD is based on Annex VIII of the IVDR. This can be broken down into two sections:

- IN the first section there are general rules for allocation. This relate, for example, to dependencies on product parts or several separate products and rules in the event of conflicts.

- The second section contains seven rules for the allocation of products to risk classes A to D.

a) Intended purpose

The application of the classification rules depends on the intended purpose of the products. With this, the manufacturer sets out the medical purpose for which their device is to be used. The intended purpose ultimately also determines the classification, depending on the risk.

The intended purpose can be found on the labeling, the instructions for use, and the advertising materials for the product. It makes the product a medical device.

This also arises from the definition in Article 2 IVDR:

Definition of “in-vitro diagnostic medical devices”

“in vitro diagnostic medical device means any medical device which is a reagent, reagent product, calibrator, control material, kit, instrument, apparatus, piece of equipment, software or system, whether used alone or in combination, intended by the manufacturer to be used in vitro for the examination of specimens, including blood and tissue donations, derived from the human body, solely or principally for the purpose of providing information on one or more of the following:

a) concerning a physiological or pathological process or state;

b) concerning congenital physical or mental impairments;

c) concerning the predisposition to a medical condition or a disease;

d) to determine the safety and compatibility with potential recipients;

e) to predict treatment response or reactions; or

f) to define or monitor therapeutic measures.

Specimen receptacles shall also be deemed to be in vitro diagnostic medical devices;”

Source: Article 2 IVDR

Read more about the purpose of medical devices in our blog Intended purpose and intended use: more serious than you think! (German)

Note

If your product is placed in a higher risk class than you expected, the intended purpose may not have been determined correctly.

b) General rules for classification according to the IVDR

The first part of Annex VIII describes general rules to ensure the dependencies and requirements for the correct classification depending on the product type.

Dependencies of products

In principle, dependencies of IVD products are handled according to the following formula:

- If products or product parts are dependent on one another, they are classified together (same risk class of the parts).

- If they are not dependent on one another, product parts or products are classified separately from one another (different risk classes of the parts).

Example of products that are classified together:

- Accessories

A digital camera can be connected to a microscope specifically intended for pathology so a second pathologist can view the histological sectional view at the same time. All of the parts are classified together.

Examples of products that are classified separately:

- Separate products

Antibody-based reagent kit and ELISA reader that do not reference one another

- Software

The following fundamentally applies to software: if a software carries out its own medical purpose then it is classified separately.

Examples and more precise descriptions of the classification of IVD software can be found in our article Classifying IVD software correctly.

Definition of accessories

“Accessory for an in vitro diagnostic medical device” means an article which, whilst not being itself an in vitro diagnostic medical device, is intended by its manufacturer to be used together with one or several particular in vitro diagnostic medical device(s) to specifically enable the in vitro diagnostic medical device(s) to be used in accordance with its/their intended purpose(s) or to specifically and directly assist the medical functionality of the in vitro diagnostic medical device(s) in terms of its/their intended purpose(s)”.

Article 2(4) IVDR

Application of the seven classification rules for class A-D

For the application of the seven classification rules from the second section of Annex VIII of IVDR, section 1 determines:

- In the case of several intended uses of a product, the entire product is placed in the highest class.

- If several classification rules apply, the rule of the highest class is used.

- Each classification rules applies for first-time tests, confirmation tests, and additional tests.

- The manufacturer must always take into account all classification and implementation rules to find out the class in which the product belongs.

Sources that help with the classification

In addition to the IVDR, there are various external sources you can use to help you decide the class to which you should allocate your product. These include:

- MEDDEV guidance from the European Commission (2.14 series): may help in the event of uncertainties in the IVDR

- Manual on borderline and classification in the Community Regulatory framework for medical devices by the European Commission: helps with distinguishing medical devices from other products

- Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF)

- IVD classifier tool by the Johner Institute (German): automatically determines the risk class, facilitating the initial assessment

c) Risk classes according to IVDR

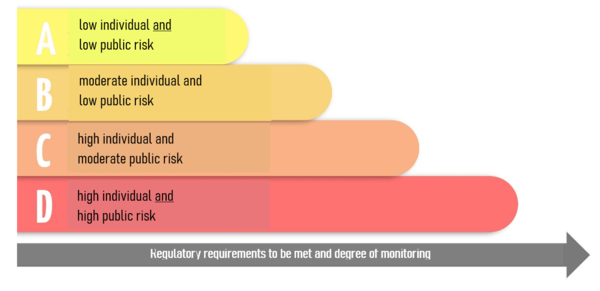

The second part of Annex VIII contains the seven critical rules for the allocation of the precise risk class. The IVDR breaks IVD down into four risk classes from A to D. The allocation depends on the hazards the IVD could cause.

All seven rules must always be taken into account. However, the rule of thumb of the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) can initially be used for the allocation. This is:

Rule of thumb for IVD classification

The greater the risk of a life-threatening disease and the larger the group of people affected, the higher the risk class.

Fig. 2: Allocation of IVD using the IMDRF rule of thumb

Class D – life-threatening infections – highest risk

High individual and high public risk

In the case of class D products, an incorrect result presents a life-threatening risk for several individuals (rules 1 and 2).

Class D includes products for:

- Evidence of transmissible pathogens that cause a life-threatening disease with a high risk of spreading (rule 1)

- Example: the detection of highly contagious and dangerous pathogens such as the Ebola, SARS, Lassa, and Marburg viruses

Warning! Depending on the intended purpose: HIV, measles, MRSA, MRGN

- Example: the detection of highly contagious and dangerous pathogens such as the Ebola, SARS, Lassa, and Marburg viruses

- Determination of the degree of infection of a life-threatening disease as part of monitoring for patient management (rule 1)

- Example: Degree of infection of tuberculosis patients

- Evidence of transmissible pathogens for the suitability of blood, cells, tissues, or organs for transfusions or transplants (rule 1)

- Example: Tests that detect the HIV, HCV, HBV, HTLV status in blood reserves

Class C – products with a high risk

High individual and moderate public risk

In the case of class C products, an incorrect result presents a life-threatening risk to an individual (rule 3).

Class C includes products for:

- Blood group determination, tissue typing of unlisted markers

- Example: HLA typing

- Determination of the immune status of women for transmissible pathogens during a prenatal screening examination (CMV tests in pregnant women)

- Diagnostic tests alongside treatment (EGFR (lung cancer), BRAF (skin cancer), KRAS (bowel cancer))

- Cancer screening, diagnosis, determination of stage (PAP test, CIN test (determination of the stage of cervical cancer))

- Genetic tests in humans (carrier testing, BRCA1/2 (predisposition to breast cancer), HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 (celiac disease))

- Genetic disorders in an embryo or fetus (NIPT (fetal trisomy, microdeletions))

- Examination of infectious pathogens with a risk of life-threatening situations if the result is incorrect

Class C/B – self-tests

IVD products for self-tests fundamentally come under risk class C (rule 4).

Example of a class C self-test:

- Indicator tests

- Sampling sets

In exceptional cases, self-tests come under class B (rule 4). This applies to products for tests close to the patient’s body.

Example of a class B self-test:

- Cholesterol test

- Pregnancy test

Class B – fallback class

Moderate individual and low public risk

In the case of class B products, there is no life-threatening risk in the event of an incorrect result (rules 6 and 7).

Class B should be viewed as a “fallback class”.

- Products that do not come under rules 1 to 5 are allocated to class B.

- Control devices with no assigned quantitative or qualitative value are allocated to class B.

Class A – laboratory requirement

Low individual and low public risk

Products in risk class A do not produce any results (rule 5).

These include:

- Instruments specifically provided for in-vitro diagnostics

- Examples: Quantitative PCR thermocycler, sequencer, mass spectrometer, ELISA reader, flow cytometer

- Specimen receptacles

- Examples: Urine pots, saliva tubes, EDTA blood sample tubes, containers for swabs

- Products for general laboratory requirements: Accessories with no critical features, buffer solutions, washing solutions

- Examples: Special buffers for preserving or pre-treating cells; special coated vessels that prevent disruptive factors for a given test

- General culture media and histological stains for specific IVD tests

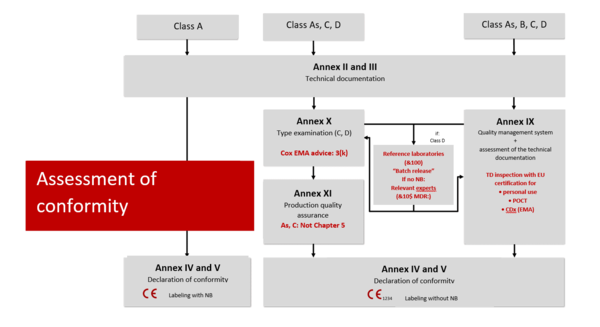

d) Consequences of the classification

The risk class determines the conformity assessment procedure.

Class D

An intensive audit is carried out in the highest IVD risk class

The reference laboratory (generally the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut) checks each batch of reagent manufactured using samples. In the case of novel IVDs in this class, the scrutiny procedure is also used (procedure in which the notified body appoints a committee of experts as part of the conformity assessment; Article 50 IVDR).

Class C

As for class B, but testing focuses in particular on the performance assessment. In the case of special products such as POCT (point-of-care testing) or self-tests, testing focuses in particular on usability. In the case of CDx, the focus of testing is on the acquisition of the medicinal product with the involvement of the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

You can find more information about product groups and categories in our article Product category, generic product group, medical device group: don’t mix them up! (German)

Class B

From class B and above the QM system is audited by the notified body and the technical documentation is checked. If you form product categories, only representative products in a category are tested.

Class A

- For class A IVDs, manufacturers do not need to involve notified bodies, in other words the documents do not need to be checked by a notified body. The documents can, however, be requested by the authorities. According to Article 10(8) IVDR, manufacturers need a full quality management system (ISO 13485).

- In the case of instruments and products that are also machines, the EMC Directive and the Machinery Directive apply (more on this in the blog Machinery Directive). In the case of sterile products such as sampling vessels, corresponding standards such as the EN 556 series apply.

Note: even class A manufacturers need a notified body to inspect these sterile aspects. Their inspection, however, is limited exclusively to this area.

Regardless of the classification, manufacturers must meet the applicable underlying safety and performance requirements set out in Annex I of the IVDR. Evidence of compliance with the latest technology must therefore be documented for all classes, including class A:

- Risk management (ISO 14971)

- Usability (IEC 62366-1)

- Verification and validation

In the case of products that are software or contain software, further evidence is needed:

- Software life cycle (IEC 62304)

- IT security

4. How to classify in a smart manner

Incorrect or at least unfavorable classification into risk classes can occur with IVDs. In most of these cases, the product ends up in a class that is too high and is therefore inspected more intensively than necessary.

This mainly occurs when manufacturers focus on the possible uses of the product and not on the defined intended purpose (in other words only the intended use). What is relevant, however, is what the product is intended for and not the uses that can occur in deviation from this.

Targeted measures and arguments can avoid the most common classification errors. We set out three typical problems when carrying out classifications according to IVDR and their possible solutions.

a) Breaking systems down into products

Problem:

With the new IVDR classification system, numerous products made up of various parts are allocated to a higher class. An analysis system, for example, moves to the highest class due to a single critical component. For most parts of the system, though, this is not necessary.

Example:

You combine an IVD analysis device, a sample preparation robot, and software to interpret the results into a system. The system is described as a whole in the technical documentation and is sold as a complete solution. The classification for the entire system is then dependent on the biomarkers tested and the clinical statement made using the system.

If the analysis system described is used to provide evidence of antibodies to determine an allergy status, this can result in an allocation to class B through rule 6. If the immune status of pregnant women with regard to a potential cytomegalovirus infection (CMV) is to be determined using the system at the same time, it belongs in class C. If the system also tests the compatibility of blood reserves for potential recipients, it comes under class D.

Solution:

Clever separation is the key to a differential classification. This leads to a more streamlined and speedier authorization scenario. The payoff for this is that you have to create technical documentation for each of the combined individual products.

You can break this system down into individual products and describe their interfaces in such a way that they achieve their purpose when they are combined. Each system component then has its own intended purpose and its own technical documentation. Then at least the analysis device comes under class A and the reagent product for the allergy status under class B.

b) Optimizing the classification with smart software architecture

Problem:

The clinical statements in the results report go well beyond the intended use as formulated. This indirectly catapults the product into a higher class or creates special cases that additionally need to be assessed by the notified body.

Example:

IVD software with the intended purpose “to determine the pathogenicity of genetic variants” comes under class C, as this is mostly cancer diagnosis or genetic tests (determination of hereditary diseases). If in addition to determining the pathogenicity of the variant the results report also suggests a medicinal product as treatment or potentially even provides information on the safety of the medicinal product in the context of the variant(s) identified, this is companion diagnostics.

This is a special case in the inspection of technical documentation. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) needs to be involved. If transplant markers are also tested for compatibility with potential recipients on the same platform, the entire product comes under class D.

Solution:

Technology platforms can be constructed as modular systems with the modules each describing separate software. This involves the creation of several technical documentation files, but the platform itself does not even need to be qualified as a medical device. Software architects who can show why the modules are independent of one another are needed for this solution.

As this example shows, in addition to its medical purpose software mostly also carries out numerous non-medical functions. The classification of IVD software is therefore extremely complex. We examined the topic in more detail in the specialist article Classifying IVD software correctly.

c) Break reagent kits down into components

Problem:

Many manufacturers offer similar reagent kits. Although the individual components overlap, they are described again for each individual kit. Many parts of the technical documentation contain redundant information.

Some manufacturers also offer kits with multiplex evidence. In this case, the highest class applies depending on the intended purpose of the critical parameter. As a result, the entire kit moves into the higher class B, C, or D based on the intended purpose.

Solution:

Most reagent kits are component-based from the outset: buffers, enzymes, analyte-specific reagents such as primers, probes, or antibodies, controls and where appropriate calibrators all work together. The kits can be broken down into components. Kit 1 then contains, for example, the generic parts and the technology (e.g. PCR). The generic part only needs to be described once, as it is always the same. This kit then comes under class A. The analyte-specific reagents then separately come under the higher classes.

This means more technical documentation is needed, but it is more streamlined and can be expanded like a modular system.

5. Tip: the Johner Institute’s IVD classifier tool

The classification of IVD products can sometimes be difficult. To simplify the process, you can now use the free IVD classifier tool (German) by the Johner Institute.

In just nine short questions, you will get an initial assessment of the risk class of your IVD. This saves you the laborious work of going through each step in Annex VIII of the IVDR.

6. Conclusion

The IVDR expands the scope of its predecessor, the IVDD. As a result, a large number of IVD medical devices are moved into a higher risk class. If manufacturers do not proceed correctly, their products will be allocated to an unnecessarily high class. This can have wide-ranging consequences.

In particular, a careful breaking down of components can avoid a higher classification of IVD products.

The key is smart separation through a precisely described intended purpose. We call this the segregation strategy (German). We know from our own experience in consultancy that it’s no easy task. We would be happy to help you with your segregation strategy.

Please do not hesitate to contact the Johner Institute if you have any questions about the segregation strategy or classification. You can use the

to do so or just send an email. You can also use the free IVD classifier tool (German) by the Johner Institute to estimate the risk classification of your IVD quickly and easily.